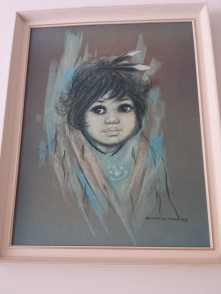

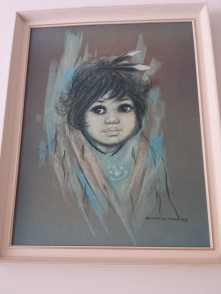

“Moana” an original work in pastel by Kristin Zambucka, 1969. Bought by my Mother in Christchurch, in 1969, and given to me last year, 2017. Now hanging in our house. The artist, Kristin Zambucka, spent most of the 1960’s and ’70’s travelling around New Zealand (with a side journey around the Pacific) in search of indigenous “subjects” to draw (pastel portraits). Zambucka focused mostly on drawing women’s portraits, and at one stage tried to capture what she called “Faces from the Past: The Dignity of Maori Age”. I have a large, and rare, book full of these portraits.

Looking at this work now it seems quaint and almost inappropriate that an artist sought to capture the likenesses of “the other” before they disappeared. My sister, an anthropologist, says that artists doing what Zambucka has done was common 40 to 50 years ago, and was the white world’s attempt to capture “the native world”, because of the differences between the cultures.

As I previously wrote, my Posts for the last MindLab assignment are out of order. This Post considers “my” indigenous knowledge and cultural responsiveness in my practice, was supposed to be written in Week 31, and represents Activity 7. So, I am very late.

My lateness though does not mean that I have not been thinking about this topic. I have been reflecting on this topic for the past three weeks, mainly because I have not known how to approach the topic, and have also been feeling confused and, I have to confess, irritated about the topic itself. I watched Milne’s ULearn (2017) video to the CORE conference. Milne (2017) asks so much of educators and makes so many challenges to the prevailing ideas around pedagogy in schools. The tone of the questions and the rationale behind them remind me strongly of the work of Paolo Freire (2005), The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. I think Milne (2017) is calling for radicalization of our learners via culturally sustaining pedagogy.

Milne (2017) is suggesting that we educators must focus on culturally sustaining pedagogy using the next three steps:

1=Empowered cultural identity

2=Academic achievement

3=Action for social change

I’m fine with this.

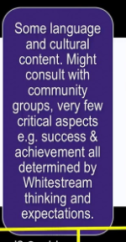

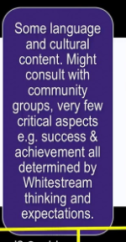

There’s a BUT though. Looking at the continuum, “Eliminating the White Spaces”, shows me that my workplace is only part way there. I think we are only at the purple box –

apart from our “separate” Maori Faculty, like a school-within-a-school, Te Ara Poutama. In my discipline area, marketing, we are not even at the “purple” box. We are stuck down the other end, the white end. Is this a problem? And why am I irritated about this final part of the assignment?

The reflective questions ask for a range of things, one of which is the extent of our own cultural understanding in our own practice. I am part-Maori, from my Father’s family. We are Ngati Apa/Nga Wairiki, from the Whanganui rohe. I was not brought up with my Maori heritage, and have only learned more in the last decade or so. We have land in the rohe, and thus a responsibility for our land and for those in the family who are also owners. Our values as a whanau do echo those of the university in which I work, but I cannot say that those values are particularly Maori. We have other values too, exemplified by my Father who speaks about the importance of hard work, trust, honesty, and fairness. These may be universal values.

And there’s the tension, for me. The values of my workplace, used in the title of this post, whilst recorded in Maori (and English) are not solely generated by Maori culture. How can they be? Many cultures share these values. If my workplace truly lived by these values, then we would see these working through the entire organisation, and there would be no division between our Maori “school-within-a-school” and the rest of us. All our learners would benefit from the way in which learning for Maori learners is personalized and structured.

So, maybe the “white spaces” continuum (Milne, 2017) works the other way around, too, where the “not-white spaces” are excluding those who previously only fit within the “white spaces”. I am also wondering about the rise of the Wananga. Have these institutions helped tertiary Maori learners advance? More so than a “conventional” western-style university? What does their “advance” look like?

Perhaps this is a little off-post, however I think there is a question to answer in the sense that Wananga represent “separateness” again, so those who are teaching at western-style tertiary institutions are excluded from learning about other, more inclusive ways because we do not have the opportunities to observe, and/or work with role models so we can aim for more culturally-responsive practice.

It’s a courageous person who critiques the prevailing wisdom. But this is exactly what Milne (2017) has done in the video calling for culturally sustaining pedagogy. If I think about my own practice, and use the research findings from Savage, Hindle et al. (2011) as a guide to assessing what I do, I find that my own practice is culturally sustaining – for Maori learners in my classes. However, I think the practices of my own organisation are not as culturally sustaining as they could be. This starts to answer the third question of the reflection for this post: What next? What can my school do to move towards more culturally sustaining practice?

On a simple level, one thing we could do is we could stop lecturing so much to our students, and start involving them more in knowledge construction (Savage, Hindle, et al., 2011). My immediate response to this, though, is “how is this so different from the flipped classroom that we are all supposed to be implementing anyway?” I don’t believe that more culturally sustaining pedagogy is only the preserve of teachers working with Milne’s (2017) continuum. I think this is about authenticity, in the classroom, in how we teach, how we help learners, and how we structure curriculum. And no one culture has a sole claim to that.

I have to stop this post, it is too long and there are too many unanswered questions. If nothing else, this particular topic has helped me think more about how I situate my practice within the culturally-diverse classrooms I work within.

References.

CORE Education. (2017; 17 October). Dr Ann Milne, Colouring in the white spaces: Reclaiming cultural identity in whitestream schools. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cTvi5qxqp4&feature=em-subs_digest

Freire, P. (2005). The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 30th Anniversary Edition. Continuum: New York.

Savage, C., Hindle, R., Meyer, L.H., Hynds, A., Penetito, W., & Sleeter, C.E. (2011). Culturally responsive pedagogies in the classroom: indigenous student experiences across the curriculum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education Vol. 39, No. 3, August 2011, 183–198.